This section of the website lists all the individual stories studied,discussed in the workshops and represented by the artists over different editions of the “Fragments of Memory: Artistic Representations of Diaspora Lives”. The art-work, bibliographic references and samples of historical sources are listed and displayed here for each single life trajectory, alongside the name of the selected scholar researching the biographies.

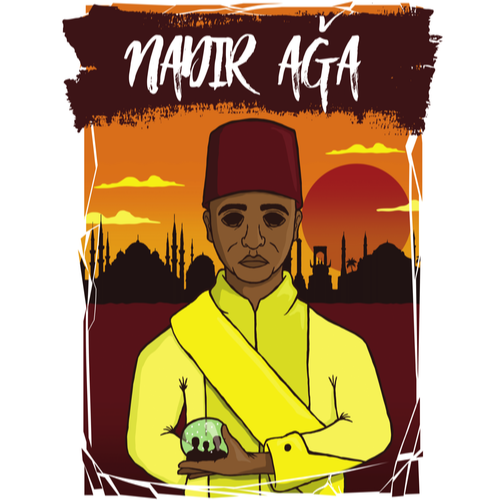

Nadir Ağa

Nadir Ağa was born in the 1870s in Galla land, Oromo region (modern Ethiopia). When he was a child, he was kidnapped and taken as a slave through the salty lake regions of Abyssinia. After being shipped from Djibouti, he was castrated and sent to Mecca to be sold as a eunuch. He spent three years serving Seyyare Hanım, a wealthy Ottoman woman, learning Arabic and receiving religious education. He was then sent north and sold as a servant to the Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II. He started serving in the Yıldız Palace in Istanbul in 1889. Being a smart young man, with a talent for diplomacy and international political etiquette, he acquired the affection of the Sultan and became one of his favorite musâhib (companions). When the movement of Young Turks overthrew the Ottoman government and exiled the Sultan thereby ending his reign, Nadir Ağa, like other slaves, was obliged to leave the Palace in 1909. His unexpected dismissal from the Palace presented him with the uncertainties of “freedom.” Nonetheless, he remained in Istanbul, where he established a dairy after he purchased forty Crimean cows. He passed away in 1957 in his late eighties in Istanbul.

Historical Images

Bibliography

Özdemir, Özgül. “Nadir Agha: A Black Eunuch from Abyssinia in the Ottoman Palace

(c.1870-1957)” in Davies, C. B.; Diouf, M.; Lovejoy, Paul E.; Santos, V. S., eds.

UNESCO General History of Africa, vol. 9, Part II. Brasília; Paris: UNESCO,

2020.

Hasan, Ferit Ertuğ. “Musahib-i sani Hazret-i Şehryari Nadir Ağa’nın hatıratı-II.

Toplumsal Tarih, 50, (1998) 6-14.

Toledano, Ehud R. The imperial eunuchs of Istanbul: From Africa to heart of Islam.

Middle Eastern Studies, 20:3 (1984), 379-390.

Primary Sources

Çapanoğlu, M. S.. “Abdülhamid’in en yakın adamı Nadir Ağa eski efendisi için neler

söylüyor,” Yedigün, 83 (1934).

“Nadir Ağa,” Hayat, 60 (1957).

Iconography

Yedigün 83, 10 October 1934.

“Nadir Aga,” Hayat 60, 29 November 1957.

Sultan Abdulhamid II hosting a

dinner at Yildiz Palace, Istanbul. Halftone by C. Hentschel, 1895, after J. Nash.

Wellcome Collection. CC BY

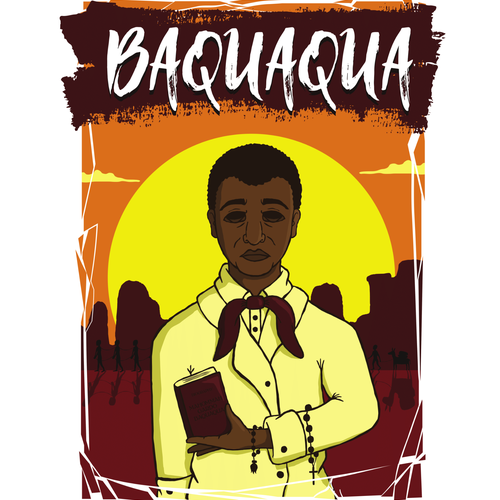

Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua

Baquaqua was born in Djougou in what is today northern Bénin around 1824. His family was prominent in the Muslim Hausa community which was involved in the kola trade between Asante (modern Ghana) and the Sokoto Caliphate (modern Nigeria). While serving as a court official, he was tricked and then enslaved for indiscretions to which he later confessed. He was quickly despatched southward through the Kingdom of Dahomey and shipped to Brazil in 1845. First purchased by a baker in Pernambuco, he subsequently became the property of a ship captain who made the mistake of taking him to New York along with a cargo of coffee. Because slavery had been abolished in New York, Baquaqua was able to escape, fleeing first to Boston and then to Haiti. Under the protection of the Free Will Baptists, he returned to the United States in 1850 to study at New York Central College. He wrote his autobiography, which was completed in Canada, as an abolitionist pamphlet that he hoped would enable him to return to Africa as a missionary. He wanted to reach Katsina, the natal home of his mother, for whom he expressed deep emotions. Whether or not he was successful is not known, although it seems he reached Liberia, at least, in 1863.

Historical Images

Bibliography

Véras, Bruno R. “The

Slavery and Freedom Narrative of Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua in the Nineteenth-Century

Atlantic World” in Davies, C. B.; Diouf, M.; Lovejoy, Paul E.; Santos, V. S., eds.

UNESCO General History of Africa, vol. 9, Part II. Brasília; Paris: UNESCO,

2020.

Law, Robin; Lovejoy, Paul E., eds. The Biography of Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua - His

Passage from Slavery to freedom in Africa and America. Revised and expanded second

edition. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2007.

Krueger, Robert, ed. Biografia e narrativa do ex-excravo afro-brasileiro. Brasília:

Editora UNB, 1997.

Véras, Bruno R. “Memórias Diaspóricas de Djougou para as Américas,” Revista

Africa(s), 1:1 (2014), 227-237.

Primary Sources

Baquaqua, M. G.; Moore, Samuel, ed. An Interesting Narrative. Biography of Mahommah

G. Baquaqua, a Native of Zoogoo, in the Interior of Africa (A Convert to

Christianity). With a Description of that Part of the World. Detroit: George Pomeroy

and Company, 1854.

Kezia King to her sisters in Hillsdale, McGrawville, N.Y., 23 October 1854.

The Liberator, August 20 (1847).

Iconography

Pamphlet cover, Mahommah Gardo Baquaqua, An Interesting Narrative. Biography of

Mahommah G. Baquaqua, A Native of Zoogoo, in the Interior of Africa (A Convert to

Christianity,) with a Description of That Part of the World; including the Manners

and Customs of the Inhabitants (Detroit, 1854) showing copyright date, August 21,

1854 (Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library).

Rev. William L. Judd, with Baquaqua from the frontispiece, A.T. Foss and Edward

Mathews, Facts for Baptist Churches (Utica, 1850).

Stereopticon card “Old N.Y. Central College – showing pupils 1848,” McGraw

Historical Society

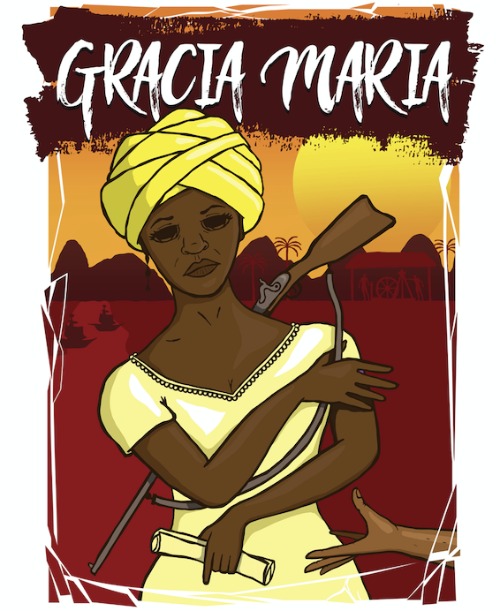

Gracia Maria da Conceição Magalhães

The place of origin for Gracia Maria Magalhães is only known as Guinea, which designated virtually all of the Atlantic coast of Africa, but most likely she was from Angola because she was taken to Rio de Janeiro. As a slave, she was known as Gracia Guiné but later was known by the same surname as her master. After she earned her own freedom, she became a member of Nossa Senhora do Rosário, and paid all the fees for the necessary sacraments that enabled her burial once she died (1789). She left a detailed account of her life as part of her will. After freeing herself, she was able to buy land in the parish of Iguaçu, build a mill and produce manioc flour. She not only freed the man who became her husband but also purchased two Angolan slaves. Gracia Maria was able to protect her land and human property from jaguars and bandits with a gun she would always have under her control. Because her body was broken by slave labor and sexual abuse, she was not able to have children. After her death, her slaves were freed and later buried in the cemetery for the Nossa Senhora do Rosário.

Historical Images

Bibliography

Bezerra, Nielson R. “Biografias de africanos na diáspora: Individual trajectories

and collective identities” in Davies, C. B.; Diouf, M.; Lovejoy, Paul E.; Santos, V.

S., eds. UNESCO General History of Africa, vol. 9, Part II. Brasília; Paris: UNESCO,

2020.

Bezerra, Nielson R. “Escravidão, Biografias e a Memória dos Excluídos,” Revista

Espaço Acadêmico, 126 (2011), 136-44.

Lovejoy, Paul. “Biography as Source Material: Towards a Biographical Archive of

Enslaved Africans,” in Law, Robin ed. Source Material for Studying the Slave Trade

and the African Diaspora. Stirling: Centre of Commonwealth Studies, University of

Stirling, 1997. 119-140.

Mattos, Hebe Maria. Das cores do silêncio: os significados da liberdade no sudeste

escravista - Brasil século XIX. Rio de Janeiro, Arquivo Nacional, 1995.

Primary Sources

Arquivo da Cúria Diocesana de Nova Iguaçu. Livro de Assentos de Óbitos e Testamentos

de Livres – Freguesia de Nossa Senhora da Piedade de Iguaçu (1777-1798)

Arquivo da Cúria Diocesana de Nova Iguaçu. Testamento de Manoel Gomes pardo forro

(1795)

Iconography

Photo by Alberto Henschel - ca.1870. Leibniz-Institut Für Länderkunde.

Jean-Baptiste Debret: voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil ou, Séjour d'un

Artiste Français au Brésil, depuis 1816 jusqu'en 1831 inclusivement, époques de

l'Avenement et de l'Abdication de S. M. D. Pedro 1er, fondateur de l'Empire

brésilien. Dédié à l'Académie des Beaux-Arts de l'Institut de France, par J. B.

Debret (Paris, 1835)

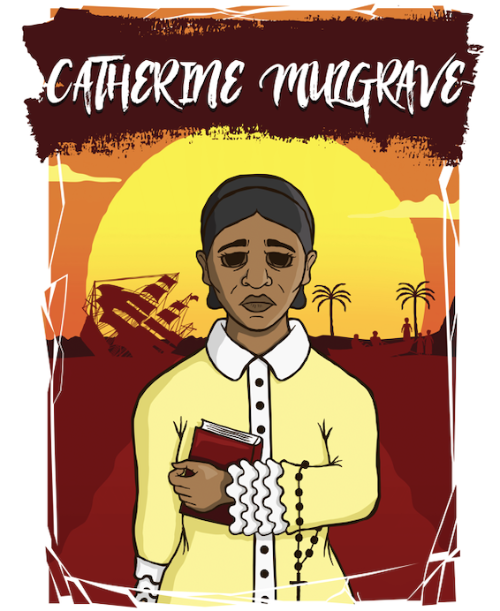

Catherine M. Zimmermann

Catherine, first names Ngeve, was born in Angola, probably in Luanda, in the early 1820s. She was kidnapped along with her two sisters in early 1833 on a beach and taken on board of a slave ship, Heroína, destined for Cuba. The ship was wrecked on the reefs off Jamaica. She and her sisters were rescued and taken to the residence of the Governor, Earl of Mulgrave in Spanish Town. In 1834, when Mulgrave and his wife left the island, Catherine was sent to the Female Refuge School at the Moravian Mission, Fairfield. She subsequently went to school in Kingston and then became headmistress at a school in Manchester. In 1842, a delegation from Switzerland arrived in Jamaica seeking recruits for a planned mission on the Gold Coast, today's Ghana. It was arranged for Catherine to marry George Peter Thompson, who as a boy had been adopted by the short-lived Basel Mission at Cape Mount in Liberia and subsequently educated in Switzerland. The couple started a school for boys and girls in what is now Accra, although Thompson was subsequently dismissed, and the marriage ended in divorce. In 1851, she married Johannes Zimmermann, recently arrived from Germany to head the mission. After Zimmermann died in 1876, Catherine continued to teach at several schools until her death in 1891.

Historical Images

Bibliography

Warner-Lewis, Maureen. “Catherine Mulgrave-Zimmermann” in Davies, C. B.; Diouf, M.;

Lovejoy, Paul E.; Santos, V. S., eds. UNESCO General History of Africa, vol. 9, Part

II. Brasília; Paris: UNESCO, 2020.

Haenger, Peter. “Ein Missionar fällt aus dem Rahmen,” Auftrag 1 (1995),

12-13.

Lovejoy, Paul E. “Les origines de Catherine M. Zimmermann: considérations

méthodologiques,” Cahiers des Anneaux de la Mémoire 14 (2011), 247-63.

Warner-Lewis, Maureen. “Catherine Mulgrave’s Unusual Transatlantic Odyssey,” Jamaica

Journal, 31:1-2 (2008), 32-43.

Primary Sources

George Thompson to Thomas Buxton, 25 January 1843 in Papers of Sir Thomas Fowell

Buxton, Reel #9 at Rhodes House Library, Oxford.

Pfeiffer, Fairfield H. G. “Report of 5 February 1846,” Periodical Accounts Relating

to the Missions of the Church of the United Brethren Established among the Heathen

18, 436.

Iconography

The Zimmerman-Mulgrave Family, unknown studio, 1872-1873 - Archiv Basler Mission

QS-30.002.0237.02.

Zimmermann, Johannes und [Ehefrau] Zimmermann-Mulgrave, Catherina, 1872-73 - Archiv

Basler Mission QS-30.002.0237.03

B.F.K.Rives Nr.75. Basel Mission High Street Accra Factor, - Archiv Basler Mission

QU-30.003.0182

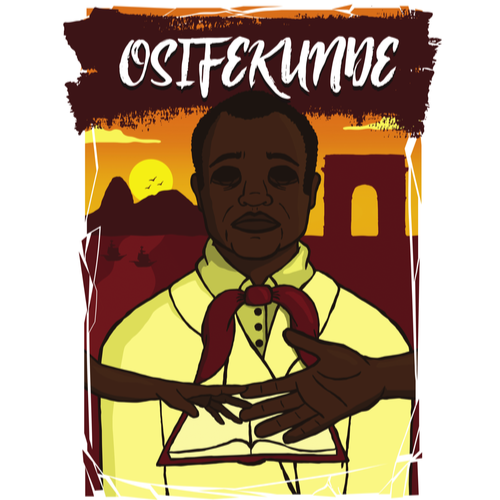

Osifekunde

Osifekunde was from an aristocratic Yoruba family from Makun in Ijebu (modern Nigeria). He was a successful merchant operating along the lagoon between Ijebu and Lagos until captured by Ijo pirates and taken to the Niger Delta, where he was sold to a Brazilian slave ship. After arriving in Rio de Janeiro in 1820, he was sold to a French sugar planter from Pernambuco. Seventeen years later in 1837, his master took him to Paris, where he came to the attention of Marie-Armand Pascal de Castera-Macaya d'Avezac, a geographer who was an archivist at the Ministry of the Navy and Vice-President of the Société Ethnologique where he was conducting research on West Africa. Arrangements were made for Osifekunde to move to Sierra Leone, but he decided to take the risk of being re-enslaved and return to Brazil where he had a son. He was a cosmopolitan black man, able to speak several languages. In 1842 a gang attacked him, shaved his head and beat him to death.

Historical Images

Bibliography

Ojo, Olatunji. Osifekunde of Ijebu (Yorubaland)” in Davies, C. B.; Diouf, M.;

Lovejoy, Paul E.; Santos, V. S., eds. UNESCO General History of Africa, vol. 9,

Part II. Brasília; Paris: UNESCO, 2020.

Lloyd, P. C. “Osifekunde of Ijebu.” in Philip D. Curtin, ed., Africa Remembered:

Narratives by West Africans from the Era of the Slave Trade. Madison, WI:

University of Wisconsin Press, 1967, 217-288.

Peabody, Sue. “There Are No Slaves in France”: The Political Culture of Race and

Slavery in the Ancien Régime. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Santana, A. R. “A Extraordinária Odisseia do Comerciante Ijebu que foi Escravo

no Brasil e Homem Livre na França (1820-1842),” Afro-Ásia, 57 (2018), 9-53.

Primary Sources

Bibliotheque Nationale du France. Catalogue de l'histoire de France, Tome 8.

Paris: Firmin Didot Freres, 1863.

D’Avezac de Castera Macaya, Marie-Armand-Pascal. Notice sur le pays et le Peuple

des Yébous en Afrique. Paris: Librairie Orientale de Mme Ve Dondey-Dupré,

1845.

D’Avezac de Castera Macaya, Marie-Armand-Pascal. Esquisse générale de l'Afrique

et Afrique ancienne. Paris: Firmin Didot Frere, 1844.

Iconography

Osifekunde, made from a life mask (Paris, ca.1838) - D'Avezac, "Notice sur le

pays et le peuple des Yébou," Mémoires de la Société Ethnologique, 2 (1845)

D'Avezac, "Notice sur le pays et le peuple des Yébou," Mémoires de la Société

Ethnologique, 2 (Paris, 1845).

Awujale (King) of Jebu Ode, Colonial Office photographic collection - The

National Archives CO 1069/80

Marie Armand Pascal d'Avezac de Castera Macaya] / Ch. Reutlinger, 1875.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Société de Géographie, SG

PORTRAIT-1432